The remains of an Illyushin Il-28 downed by Peshmerga forces in Galala in 1965. The aircraft appears to be one of the Russian-made fighter jets purchased by the Iraqi Air Forces in 1958. Photo: Mohammed Ali

ERBIL, Kurdistan Region — When Kurdish journalist Aso Haji visited Paris in 2010, the only highlight he expected was an opportunity to interview the Foreign Minister of France, Bernard Kouchner. Instead, he discovered that a treasure trove of Kurdish history – negatives of more than 200 photographs taken more than half a century ago – were still intact, in France.

After years spent searching, the remarkable photographs and the story behind them have been brought to light in Haji’s new book, From Paris to Tayrawa.

The search began at the Kurdish Institute of Paris, where founder Kendal Nezan told Haji that a French writer named Jean Pradier had dedicated his dissertation research to the Aylul Uprising. Led by Mullah Mustafa Barzani, the period Kurds refer to as the "September Revolution" lasted 14 years from 1961 to 1975. Visiting the Kurdistan region in 1966 to meet with Barzani and other revolutionary leaders, Pradier’s studies resulted in a book, Les Kurdes: Revolution Silencieuse (The Kurds: Silent Revolution) published in 1968.

That hint gave Haji a trail to follow, so he extended his stay in Paris to meet with Pradier in person. Gratefully obliged, he agreed to be interviewed for a short documentary by Haji, before handing over the prized photo negatives to Kurdish hands for posterity and safekeeping.

The discovery was stunning, but it was time for Haji to catch his flight home from Paris. The photographs documented a turning point in Kurdish history – but taking the undeveloped film through airport’s x-ray scanners risks damaging or erasing the precious images. The journalist felt a fire under his feet, and without another thought, decided to swallow the expense and stay another week in Paris to develop the photos.

The man behind the camera

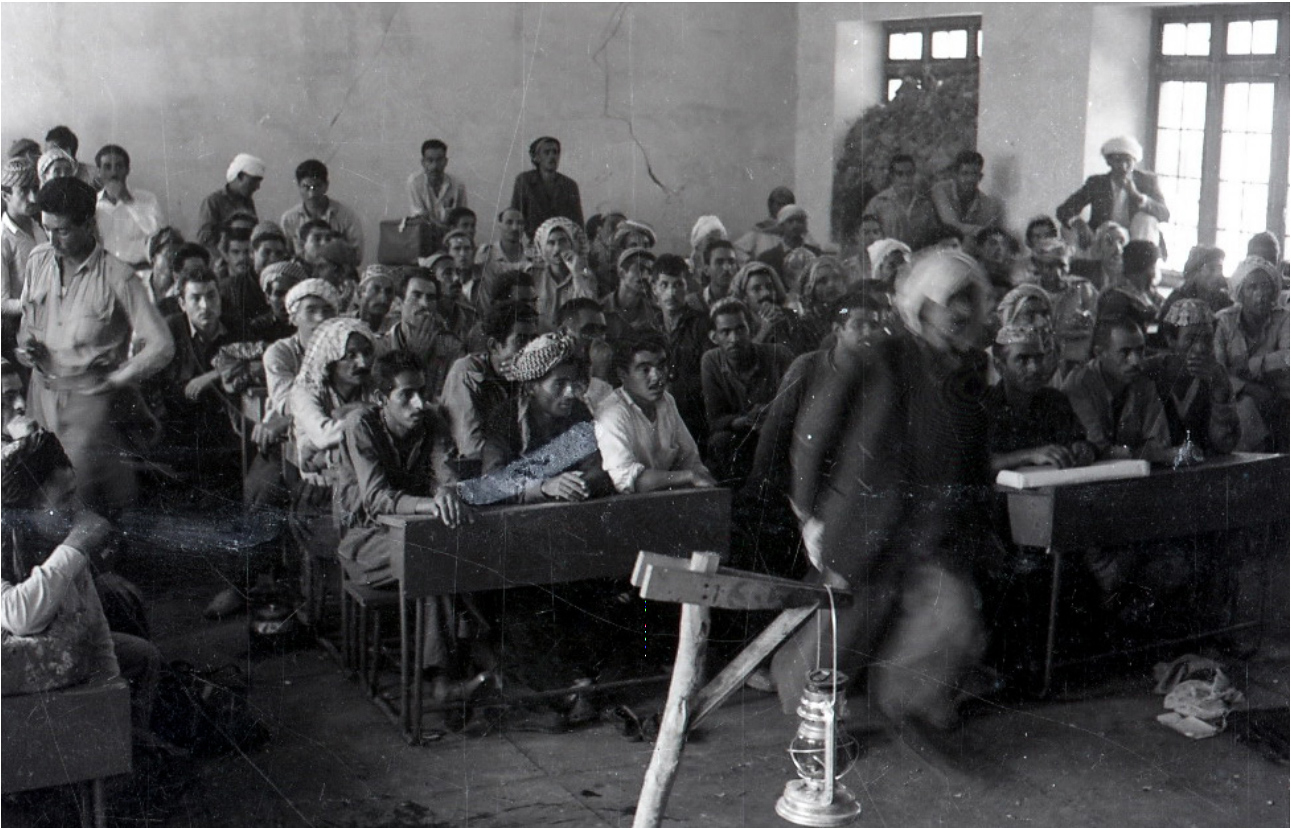

The photos unearthed a colorful and bright history, offering a distant glance into village life during the Aylul Uprising. They showed what looked like be important meetings between foreign delegations and Kurdish Peshmerga forces at the fighters’ headquarters in the mountains between Iran and Iraq.

Haji returned to the Kurdistan Region to find a publisher for a book he would write based on the photographs. Success would evade him for years, until he met with Ako Mohammed, CEO of Rudaw Media Network, in 2019. With a supportive sponsor, he could continue in pursuit of the uncharted path of history that had kept him captivated for years. But questions remained. He know what was shown in the photos – but who was behind the camera, and how had they managed to be present at so many key moments of Kurdish history in that time?

The hunt for the mysterious photographer led Haji once again to Paris, to find Pradier. But that only gave him traces of a clue: Pradier could not remember his name – but he could, however, describe the photographer’s shop.

Haji searched every vintage photography shop in Erbil. That led to Barzan Mullah Khalid, a former presenter at the Voice of Kurdistan, who identified the mysterious photographer as Mohammed Ali. The two were companions, and usually scrambled at the opportunity to take photographs of leaders and Peshmerga fighters when they visited Nawpirdan, near Choman on the border between Iran and Iraq.

“Mister Mohammed was a very decent man, he was not a troublemaker,” recalls Barzan Mullah Khalid in Haji’s book. “He did great work, as archives were very rare in that time.”

But Haji still had questions. He was not satisfied with the scraps of information he had managed to obtain on the photographer, Mohammed Ali. The picture was incomplete. Ali must have been a favorite photographer of the revolutionary leaders, as he seemed to be always present whenever a delegation visited Barzani and his men. But persisting in his search and speaking to veterans among the photographers in Erbil, they helped him to eventually find Ali's son, Barzan.

Barzan took the curious journalist to the house where his father lived and worked. Quaint, roughly 100 square meters. the house is believed to have been built in the 1950s. Though no longer in use, when Haji visited, the belongings and photography equipment were still there, as if waiting for him.

Standing in the photographer’s studio after nine years of searching for clues, Aso felt that his work was finally done. “I stared at the portrait of the photographer for a while and said to myself that I finally achieved what I wanted – I felt thrilled and victorious, like a heavy burden was lifted,” Haji writes in his book, which is published by Rudaw Media Network.

.png)

Ali died in his home in Tayrawa in 1993. But through his photography, he left behind a piece of Kurdish history that was nearly forgotten.

Reporting by Karwan Faidhi Dri

Editing by Shawn Carrié

Comments

Rudaw moderates all comments submitted on our website. We welcome comments which are relevant to the article and encourage further discussion about the issues that matter to you. We also welcome constructive criticism about Rudaw.

To be approved for publication, however, your comments must meet our community guidelines.

We will not tolerate the following: profanity, threats, personal attacks, vulgarity, abuse (such as sexism, racism, homophobia or xenophobia), or commercial or personal promotion.

Comments that do not meet our guidelines will be rejected. Comments are not edited – they are either approved or rejected.

Post a comment