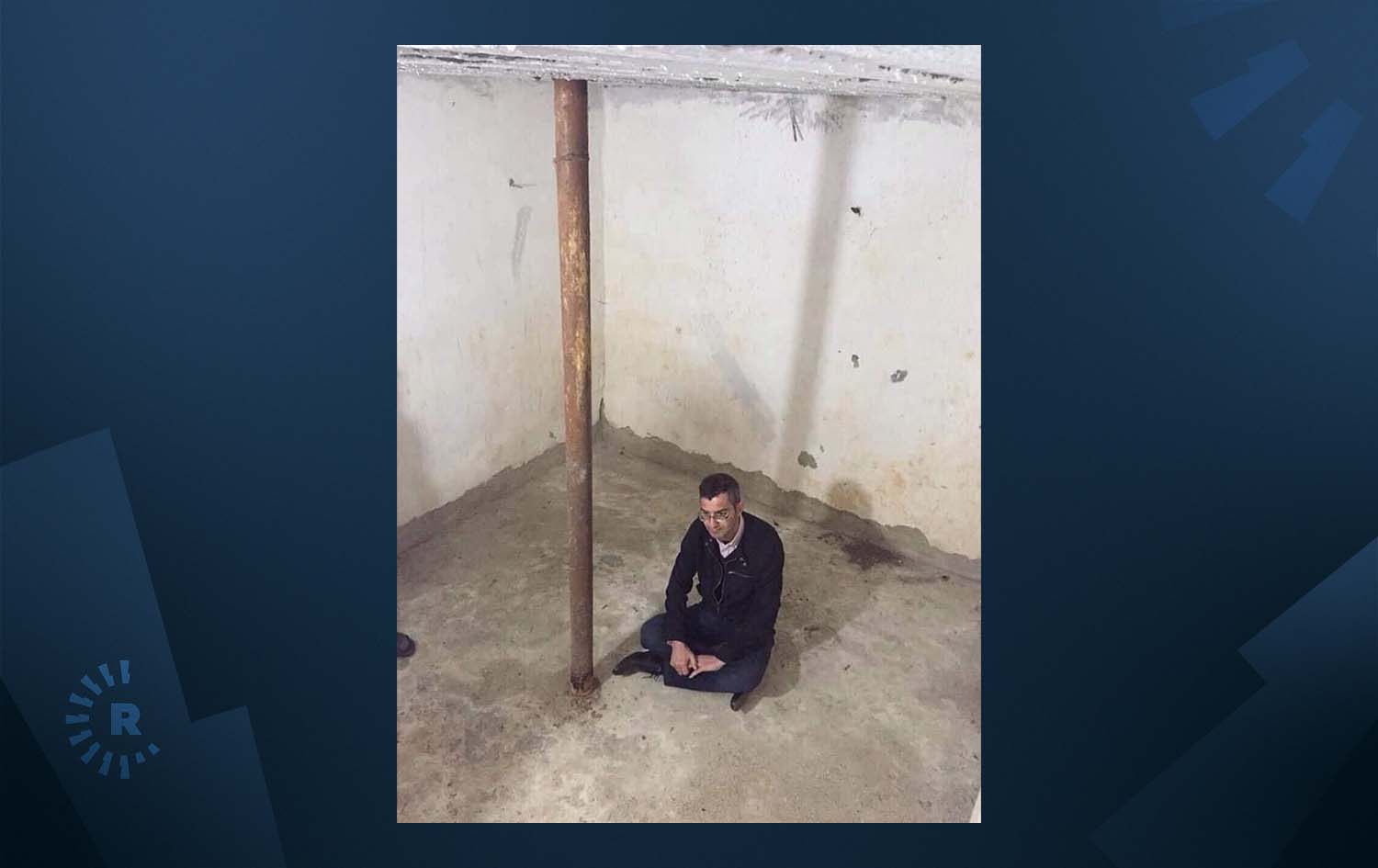

Photo of the doorstep of Kamaran Nawroz's house following the Halabja chemical attack in 1988. Photo: Submitted to Rudaw

ERBIL, Kurdistan Region - It was a sunny morning in the city of Halabja, then eleven years old Kamaran Nawroz had grown familiar to the sound of bombs and mortars as their city had been the forefront of the eight-year-long Iran-Iraq war, when sounds of bombs shook the city once again that morning, his father immediately gathered him and his five siblings into the basement he had built a year earlier for shelter, not knowing that they had made a grave mistake. The bombs that hit the city that morning contained fatal chemicals that would soon fill the air.

Control of Halabja had been seized by the Kurdish Peshmerga forces, assisted by Iran, three days earlier. Peshmerga fighters could be seen strolling the city on March 13, along with Iranian soldiers, triggering an alarm among the city’s residents that something dangerous was to come. They knew that the dictator who ruled the country at the time, Saddam Hussein, would not just stand and watch the Kurds ally with the nation’s enemy.

The fear of what was to come was in order.

On the night of March 14, Saddam’s bombs fell over the city and Kamaran’s family, along with the neighbors, sought shelter overnight in the three by four square meter basement, and despite their neighbors attempting to leave the city the next day, they claimed they were turned back as the Peshmerga had blocked the exit of the city.

The city was engulfed in chaos for three consecutive days, only to get worse around the noon of March 16, when Iraqi warplanes resumed bombardment on the city.

“We ran into our basement along with our neighbors, there were over thirty people in that small basement,” Kamaran told Rudaw English on Wednesday, with side effects of the chemical attack still apparent in his heavy breath. “Bombing continued for a few hours and then we started smelling a mixed scent of garlic and apples.”

The realization that the attack was not like the ones they had endured over the past eight years drove everyone into a state of commotion, and Kamaran then saw a scene he still pictures very well in his mind to this day, seeing his father cry for the first time in Kamaran’s life.

“I was in shock, I had never seen my father cry until then, my mother had ran out and brought us water and towels to wrap around our faces,” he said with pain still lingering in his voice. “My mother then ran after my brother who had left a few minutes earlier to check on the neighbors and she came back screaming ‘Rebwar is dead’, she fell on the stairs of the basement and never woke up again.”

Over the next hours, the bombing stopped and the elders left the basement, telling the children to stay.

Screams filled the streets of the city then slowly dimmed into complete silence.

Everyone was dead except Kamaran who was lying down in a corner of the basement, eyes almost completely blinded, with his body burnt and weak.

Kamaran woke up the next morning in the basement hearing the sound of a camera, unable to move or see, could not make a signal that he was still alive, and the photographer, who he describes as speaking a foreign language, soon left the basement without realizing there was a surviving child there.

“I then heard people speak Persian, I used the last bit of energy I had to slightly move my hand, and they saw it,” he said. “I was put in the back of a pickup truck, and I could feel it strolling the streets and picking up people who were alive.”

Kamaran was then put on board of a helicopter, and woke up in Kermanshah hospital in Iran where he received treatment.

After being transferred to a camp in the city of Harsin in Kermanshah province a few months later, Kamaran was reunited with his grandmother and uncle’s wife, who had also survived the attack.

Recognized as an act of genocide by Iraq's Supreme Court in 2010, the attack has left a permanent mental scar, not just on survivors of the attack, but on the entirety of the Kurdish nation.

Many survivors suffered long-term health problems as a result of the attack, which was just a part of a larger campaign of mass killing against Kurds in Iraq by the Baathist regime.

Kamaran returned to Sulaimani where he spent his life until 1999. He then travelled to the UK, and has been residing in the city of Portsmouth ever since, receiving treatment and checkups every six months.

Around 5,000 people, the majority women and children, were killed when Saddam Hussein’s regime dropped mustard gas onto the city of Halabja on March 16, 1988.

Saddam, overthrown in 2003 after a US-led invasion, was hanged in 2006, after being found guilty for ordering the Dujail massacre, in which 148 Shiite Muslims were killed.

Though Saddam’s execution was met with celebrations in the streets across Iraq, his death put an end to proceedings against him for the deaths of 180,000 Kurds, including those killed in Halabja, during the Anfal campaign of the late 1980s.

Kurdish officials have for years called on Baghdad to compensate the victims of the genocide, and while Kamaran believes compensation would never mend their wounds, it would offer them a slight amount of relief.

“Nothing will ever be worth the blood of my mother, but Kurdish and Iraqi officials need to treat Halabja differently as it sacrificed a lot, and compensation might help soothe the pains of all the families,” he said.

Comments

Rudaw moderates all comments submitted on our website. We welcome comments which are relevant to the article and encourage further discussion about the issues that matter to you. We also welcome constructive criticism about Rudaw.

To be approved for publication, however, your comments must meet our community guidelines.

We will not tolerate the following: profanity, threats, personal attacks, vulgarity, abuse (such as sexism, racism, homophobia or xenophobia), or commercial or personal promotion.

Comments that do not meet our guidelines will be rejected. Comments are not edited – they are either approved or rejected.

Post a comment