In late May, the Federal Government of Iraq’s Ministry of Finance issued an official letter claiming that the Kurdistan Region’s total expenditures - including public servant salaries - had been fully covered for the year, despite only having disbursed funded for four months. The Ministry’s conclusion was reached based on adding and subtracting three years’ worth of the Kurdistan Region's budget share, as well as tallying Iraq’s total debt from 2015 to the present, essentially reducing a complex fiscal relationship to a numerical justification for cutting the Region’s budget.

However, the crisis does not begin or end with the letter from the Iraqi Ministry of Finance, but has rather persisted for ten years. To truly understand its depth, one must return to the root of the problem and critically examine the numbers.

For instance, over the past decade, the Kurdistan Region’s education sector has largely operated through non-contracted, and more recently, contract-based teachers. Its health sector has relied heavily on unpaid volunteers, many of whom have worked without daily stipends. In stark contrast, during that same period, Iraq’s education sector appointed more than 319,000 teachers and education staff between 2013 and 2023. In the health sector, Baghdad hired more than 261,000 new doctors and employees - amounting to more than half a million new public servants in just two sectors.

In total, the federal government of Iraq has appointed over one million new civil servants in the last decade. In contrast, the number of public employees in the Kurdistan Region declined by nearly 20,000.

As of now, public sector salaries for May remain unpaid in the Kurdistan Region, while federal retirees across Iraq have already received their June pensions. The total amount allocated to the Kurdistan Region over the first four months of 2025 - according to the same letter from the federal Ministry of Finance, which outlined the entire budget for 2025 - is nearly half of what was spent on the Popular Mobilization Forces (Hashd al-Shaabi) during that time.

The crisis has once again intensified, accompanied by escalating rhetoric and mututal accusations between Erbil and Baghdad. These tensions will inevitably have consequences, both immediate and long-term. Temporary fixes will no longer suffice, nor would a decision from Iraq’s highest judicial authority - the Federal Supreme Court – to resolve this persistent crisis between Erbil and Baghdad.

Deferring the resolution of these financial disputes until after the November 2025 parliamentary elections is also not a viable option. Instead, a transparent approach grounded in actual data from Iraq’s Ministry of Finance is urgently required. In this article, we present the key figures and outline two core options for addressing this persistent and deepening financial rift.

Disparities in public sector employment and spending between Iraq and the Kurdistan Region

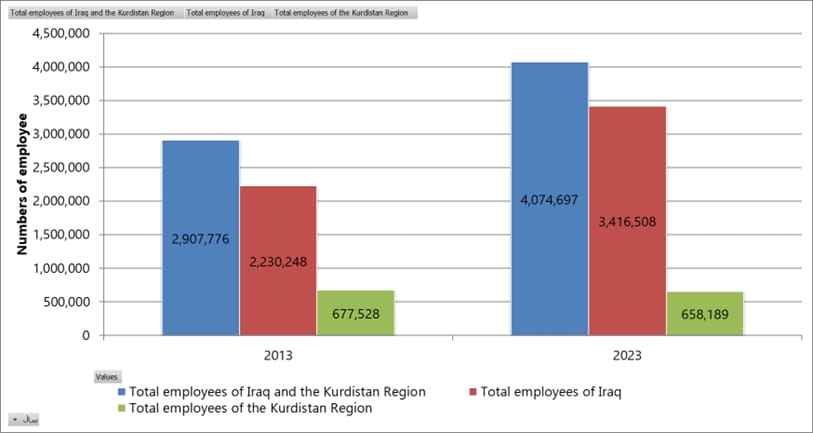

According to Iraq's approved budget law in 2013, the total number of public sector employees across all institutions in Iraq and the Kurdistan Region stood at 2,907,776. Of this total, 677,528 were employees in the Kurdistan Region. At the time, this meant the Kurdistan Region accounted for 23 percent of Iraq’s public sector workforce.

A decade later, the three-year budget law for 2023–2025 shows that the total number of public sector employees in Iraq, including the Kurdistan Region, has risen to 4,074,697. However, the number of employees in the Kurdistan Region has actually declined to 658,189. This marks a 7 percent decrease in absolute numbers and a drop in the Region’s share of the national public workforce to just 16.15 percent.

Additionally, over the past ten years, 1,182,260 new employees have been appointed across federal institutions and governorates in Iraq. In stark contrast, the Kurdistan Region has experienced a net reduction of 19,339 public sector employees over the same period.

Taking the health and education sectors as examples, the differences between Iraq and the Kurdistan Region’s public service systems become even more pronounced.

In the Kurdistan Region, medical school graduates remain unappointed, delaying their path to becoming licensed doctors. The Region’s health sector has come to rely on a system of “continuous committed volunteering,” with over 11,000 volunteers working without formal employment. In contrast, Iraq’s federal health sector employed 227,166 individuals – including doctors - in 2013. By 2023, that number rose to 488,550, meaning 261,384 new doctors and healthcare employees were hired - none of whom have ever experienced delays in salary payments.

Over the span of a decade, in the education sector, the Kurdistan Region had 37,930 non-contract teachers working without official employment status for years. These individuals were only formally contracted in 2024, with salaries now ranging between 400,000 to 500,000 Iraqi dinars (approximately $286 to $357), paid exclusively from the Region’s own internal revenues.

By contrast, Iraq’s federal education sector employed 614,613 individuals in 2013. By 2023, that figure reached 963,949, reflecting the appointment of 319,336 new staff in just a decade. Arguably, the most notable distinction between the two systems is the language of instruction - Kurdish in the Kurdistan Region and Arabic in federal Iraq.

In terms of security, in 2013 the total number of employees in Iraq's Ministry of Interior stood at 661,914. By 2023, this number had risen to 701,446. Similarly, the Ministry of Defense workforce grew from 322,297 employees in 2013 to 453,951 by 2023. This equates to 171,186 new hires in Iraq's security sector during the past decade.

In 2013, the total salary expenditure across Iraq, including the Kurdistan Region, stood at 42 trillion 587 billion 798 million dinars (approximately $30.4 billion). However, by 2023, the total salary payments for Iraq’s public sector employees – excluding the Kurdistan Region - had increased to 47 trillion 216 billion 759 million dinars (approximately $33.7 billion), marking a rise of over 4 trillion 626 billion 961 million dinars (approximately 3.3 $billion) in salaries, without allocating a single dinar to the Kurdistan Region.

Furthermore, it is predicted that in the coming years, Iraq’s revenue will be just enough to cover salary expenses. According to data from the federal Ministry of Finance, the total salary expenditure for Iraq and the Kurdistan Region in 2012 stood at 35 trillion 848 billion 747 million dinars (approximately $25.6 billion). By 2024, that number had reached 60 trillion 53 billion 380 million dinars (approximately $42.9 billion), despite a decline in Kurdistan Region public employees and the absence of salary payments to them that year.

This raises a critical question: what accounts for the additional 24 trillion 204 billion 633 million dinars (approximately $17.2 billion) in salary expenses alone? And more importantly, how should the Kurdistan Region respond to these figures?

Should it continue compiling detailed salary lists, navigating a multi-layered bureaucratic process, and waiting for approvals from Iraq’s Minister of Finance and Prime Minister, in coordination with the governing parties? Or is there an alternative approach – one rooted in transparency, equity and a redefined fiscal relationship between Erbil and Baghdad.

.jpeg)

Strategic pathways for the Kurdistan Region to address its decade-long salary dispute with Baghdad

Over the past decade, the Kurdistan Region has experienced three distinct phases in managing public sector salary expenditures in coordination with Baghdad. The first phase was marked by salary delays, the second by defined salary cuts and internal adjustments, and a third phase involving negotiated, though often inconsistent, agreements with the federal government.

To truly understand the impact of these phases, one must turn to those directly affected, asking a public sector salary recipient in the Kurdistan Region about their living conditions, perhaps a retired teacher, a gardener from the municipalities’ ministry, or an agriculture ministry employee who depends entirely on public income. Their daily struggles reflect the broader reality of how families across the Region have managed to meet basic needs amid years of financial instability.

Under the current three-year federal budget, the Region is entitled to 12.67 percent of Iraq’s total budget. By the end of April 2025, this allocation - excluding any development or investment funding - totaled 3 trillion, 664 billion, and 213 million Iraqi dinars (approximately $2.6 billion). This amount also included deductions for Iraq’s accumulated debt since 2015, even though none of those debts were incurred on behalf of, or spent in, the Kurdistan Region. Nonetheless, the Region was held accountable for them under federal accounting standards.

Meanwhile, the latest population census places the Kurdistan Region’s population at 6,370,688. Despite this, the funds allocated to the Region represented just 59 percent of what was spent expenditure allocated to the Popular Mobilization Forces (Hashd al-Shaabi) during the same four-month period, which received 1 trillion, 502 billion, and 559 million dinars (about $1.06 billion).

In moving forward, the Kurdistan Region faces two primary strategic paths for resolving its salary crisis. The first is an internal restructuring of the public sector, including a comprehensive reassessment of revenue and expenditure. If pursued, a critical first step would be the monthly publication of detailed reports on financial inflows and outflows, revenues and expenditures, eventually leading to the creation and release of a full annual budget for the Kurdistan Regional Government. This would enhance transparency, improve fiscal management, and lay the foundation for more sustainable governance.

The second option is to engage in comprehensive negotiations with Baghdad driven by data from the past two decades and conducted within a clear, time-bound framework, involving the actual decision-makers - not just representatives of the federal government. Such negotiations must also address unresolved structural issues, including the oil and gas dossier and the Kurdistan Region’s fair share of Iraq’s national budget, covering both operational and investment spending. The Kurdistan Region’s own budget should be integrated within Iraq’s annual federal budget in a formal and mutually agreed-upon process.

Regardless of the path taken, any resolution must be grounded in transparency, fairness, and accountability - moving beyond temporary fixes toward a long-term, equitable solution for all citizens.

Conclusion

Iraq and the Kurdistan Region must reconcile not only on economic issues but on a deeper constitutional and structural level. Under the current mode of engagement, these unresolved issues will not only persist but will likely deepen further - especially as Iraq faces mounting crises, including the escalating impacts of climate change.

Additionally, Iraq's Ministry of Finance ought to fulfill its financial obligations toward the Kurdistan Region at a lower cost, while also controlling its revenue and expenditure systems. On the other hand, the current approach – where the Kurdistan Region transfers only 50 to 80 billion Iraqi dinars (approximately $35–$56.6 million) in non-oil revenues to Baghdad and expects to receive nearly half of its federal budget share, mostly earmarked for salaries - is unsustainable and insufficient for resolving the broader crisis.

Now, more than two decades since the fall of the Baath regime, there is an urgent need to resolve all outstanding issues between Erbil and Baghdad within a clear and binding timeframe. These include the Kurdistan Region’s share of the national budget, the status of disputed territories and implementation of Article 140, the oil and gas file and related legislation, the formation of the Federal Council, compensation for victims of the Baath regime in the Kurdistan Region, and the clarification of constitutional provisions regarding the division of powers between the federal government and the autonomous region.

Without concrete and practical steps toward resolution, Erbil and Baghdad risk repeating the cycle of post-election political agreements aimed at forming a federal government with the Kurdistan Region’s participation - agreements that ultimately serve as temporary fixes, like the previous one that called for an oil and gas law to be passed within the first six months of the current cabinet, yet failed to produce even a draft from the federal oil ministry.

It is a misconception for the federal government to believe that it has met its obligations simply by minimizing political friction with the Kurdistan Region while manipulating expenditures and revenues through selective additions and deductions. Sending public sector salaries is not enough. In fact, the Kurdistan Region’s non-oil revenues should not have reached 2.07 trillion Iraqi dinars (approximately $1.4 billion) in the first six months of 2023 [1] – averaging around 345 billion Iraqi dinars (approximately $244 million) per month. By April 2025, this figure had fallen sharply to just 50.5 billion Iraqi dinars (approximately $35.7 million).

The facts are clear and based on available figures that if the Kurdistan Region is part of federal Iraq, then it must receive its fair share of the 49 trillion Iraqi dinars (approximately $34.6 billion) in federal investment expenditures. The starkest example of neglect is in the oil and gas sector. From the 23 trillion Iraqi dinars (approximately $16.2 billion) allocated to the Ministry of Oil as part of that investment budget over the past two years, the federal government could have - in the spirit of federal responsibility or even through a loan - established a national oil and gas company for the Kurdistan Region. At least 3 trillion Iraqi dinars (approximately $2.1 billion) could have been invested in the Miran and Topkhana gas fields in western Kurdistan to generate urgently needed electricity for all of Iraq.

Looking ahead, Iraq will continue to face a range of political, security, social, and environmental challenges - from water scarcity and rising expenditures to declining revenues. In such a context, the focus must shift toward reconciliation and reconstruction - not continued division and deterioration.

While the Kurdistan Region clearly needs urgent economic restructuring, it is Iraq that requires it tenfold. It is untenable for the federal government to reactively cut the Region’s salaries during oil price declines and then retroactively claim non-compliance based on manipulated three-year averages. If that were truly the case, why did Baghdad transfer salaries for eleven months in 2024 and four months in 2025?

In conclusion, Iraq is now entering a critical period. If federalism is to remain a viable system, then meaningful and timely action is essential to repair the relationship between Erbil and Baghdad. But if the constitutional foundations underpinning the federal arrangement between Iraq and the Kurdistan Region have been effectively been abandoned, then it is incumbent upon the Kurdistan Region to take the initiative and begin resolving its internal challenges independently, charting a course forward based on transparency, self-reliance, and structural reform.

Mahmood Baban is a research fellow at the Rudaw Research Center.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of Rudaw.

Comments

Rudaw moderates all comments submitted on our website. We welcome comments which are relevant to the article and encourage further discussion about the issues that matter to you. We also welcome constructive criticism about Rudaw.

To be approved for publication, however, your comments must meet our community guidelines.

We will not tolerate the following: profanity, threats, personal attacks, vulgarity, abuse (such as sexism, racism, homophobia or xenophobia), or commercial or personal promotion.

Comments that do not meet our guidelines will be rejected. Comments are not edited – they are either approved or rejected.

Post a comment