Recent discussions about a supposed shortage of dinars—affecting the November salaries in Iraq’s central and southern provinces and the September salaries in the Kurdistan Region—require clarification. The facts become clear when examining the figures from the Central Bank of Iraq (CBI), the Ministry of Finance, and the Ministry of Oil.

It is important to distinguish between a cash shortage at the CBI and a dinar shortage at the Ministry of Finance. These are not the same. The data shows that the CBI is not running out of dinars; on the contrary, it has actually reduced its currency issuance.

The real issue lies within the Ministry of Finance, where the gap between revenue and expenditure has widened significantly. As a result, the first and most immediate place where cuts or delays have appeared is the Kurdistan Region.

Iraq is an oil-dependent country, which means its revenues and expenditures are driven primarily by oil prices rather than by government planning or the annual state budget. According to the CBI, oil has accounted for 99 percent of total exports, 85 percent of the national budget, and 42 percent of domestic product growth over the past decade. Although the Bank reports a slightly lower share in terms of revenue, the reality in recent years is that oil income has exceeded 90 percent of total state revenue.

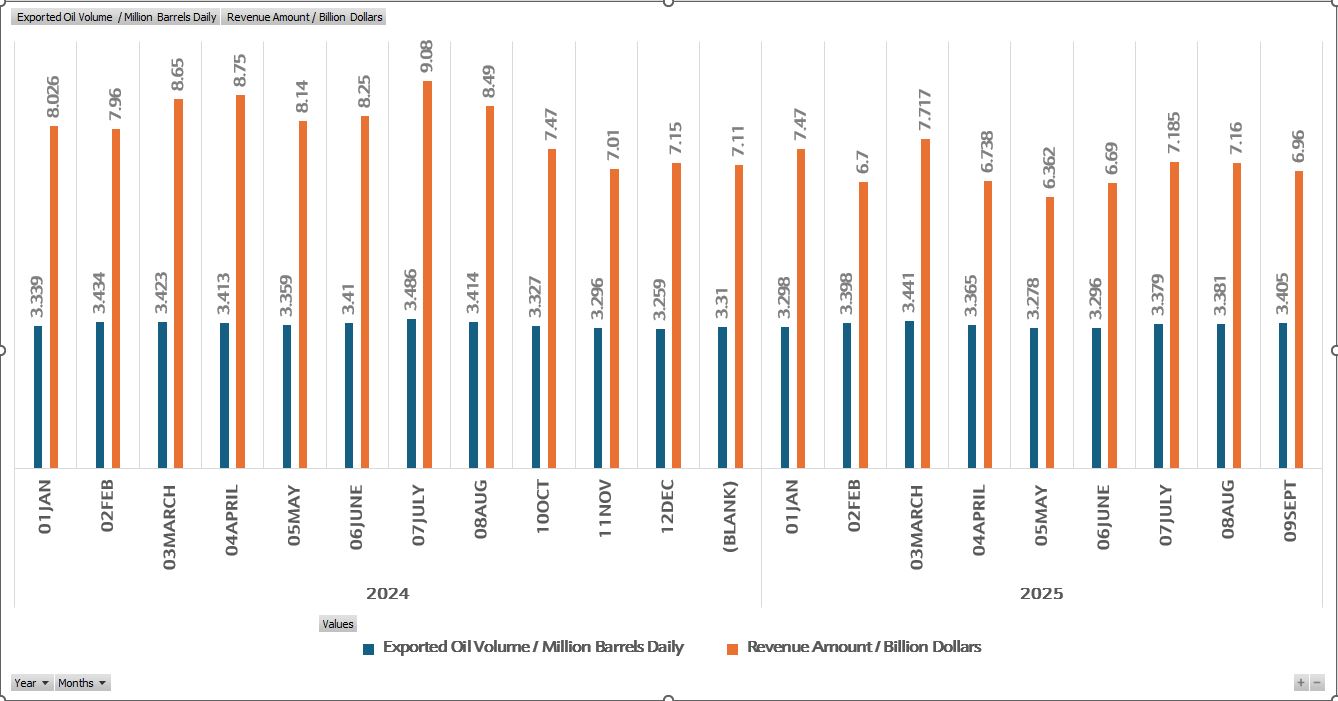

In practice, Iraq’s economic governance is shaped far more by fluctuations in global oil prices than by the annual budget law or any five- or ten-year development plans. For example, over the past nine months, the Ministry of Oil has reported revenues of $62 billion. Based on these figures, the CBI has supplied 81 trillion dinars to the Ministry of Finance’s treasury—an amount notably lower than the 97 trillion dinars the Ministry of Finance spent during the same period, exposing a significant gap between revenue and fiscal needs.

According to data from the CBI, the country is not facing a cash shortage or a lack of dinars. In fact, as part of its monetary policy, the CBI has reduced liquidity in circulation by 4.5 trillion dinars over the past year. For example, in September 2024, the total volume of Iraqi currency issuance declined from 104 trillion dinars to 99 trillion dinars. Most of this decrease came from dinars withdrawn from the currency outside banks rather than from currency held by commercial banks, as shown below.

The cash policy of the CBI is closely tied to oil revenues. As shown in the third graph, oil revenues begin to decline from September 2024 onward. In response, the Bank correspondingly reduces the amount of money it issues, as illustrated in Graph 1. This demonstrates that fluctuations in oil prices directly shape Iraq’s monetary policies, compelling the CBI to adjust the volume of money movement both outside the bank and within the commercial bank.

The current issue is the month-by-month decline in the Ministry of Finance’s revenues—which come primarily from oil—not a shortage of cash, as is often claimed publicly. As illustrated in the graph below, if expenditures in September alone reached 8 billion dollars, then the gap between revenues and expenditures for the first nine months of the year has surpassed 4.4 billion dollars.

Over the past two years, the Ministry of Finance has covered this shortfall through domestic debt. As a result, domestic debt rose from $55 billion at the end of 2023 to $67 billion by the third quarter of 2025, an increase of roughly 21 percent of domestic debt during that period.

However, debt cannot continue indefinitely and cover the deficits because persistent deficits and debts will eventually turn year-end revenues into debt obligations. The gap must be addressed through expenditure reductions, not by continuously increasing debt. Unfortunately, the first area targeted for cuts has been the delay of the Kurdistan Region’s salaries, despite the region fulfilling its commitments by delivering both oil and domestic revenues.

.jpeg)

Note: Revenue and expenditure figures for September 2025 are calculated as the average of the eight preceding months.

According to data from the Ministry of Oil and the Ministry of Finance, monthly oil revenues amount to $6–7 billion, depending on the price. However, in recent months, the Ministry of Finance’s expenditures have reached $10 billion per month, rather than the usual $8–9 billion. As this gap widens, the financial burden falls on the Ministry of Finance, not the CBI. The Bank can only provide dinars in proportion to actual revenue, not in proportion to government spending. For this reason, as shown in the first graph, Iraq’s cash policy reflects a reduction—rather than an expansion—in dinar issuance.

When expenditures rise while revenues decline, a deficit naturally emerges. In such a situation, external borrowing and debt become impossible, and domestic debt provides little relief. At that point, the problem manifests as a shortage of dinars at the Ministry of Finance, not at the CBI. This is because the spending in question is not investment-related. Banks and financial institutions cannot finance or cover deficits that are directed toward salaries, social welfare payments, bonuses, aid programs, and energy subsidies—items that generate no financial return. These non-investment expenditures have reached 102 trillion dinars in a single year.

The situation of the Kurdistan Region is particularly striking. In this government—compared with previous years, previous cabinets, and even recent periods—the Kurdistan Region has delivered its oil and transferred its non-oil revenues. For the past two months, SOMO has been selling the Region’s oil, totaling 5.8 million barrels last month. The average daily export of Kurdish oil has been 200,000 barrels in November. Together, this exceeds 11 million barrels, generating approximately $700 million—or 900 billion dinars—at the Ceyhan Port price for Iraqi oil.

In addition to this, the Region has transferred 120 billion dinars in non-oil revenues, contributing, on average, 9.4 percent of Iraq’s total non-oil revenue. Yet, despite these contributions, the September salary for the Kurdistan Region has yet to be released, while the federal government has already begun disbursing November salaries for the central and southern provinces.

In short, the narrative about a “lack of cash” is misleading. The real issue is declining revenues and rising expenditures. When national spending is consumed by salaries, social welfare, bonuses, assistance programs, and energy subsidies—even oil sold at $70 or $80 per barrel cannot cover the cost.

Finally, the CBI cannot fill a deficit exceeding 15 trillion dinars accumulated over nine months by the Ministry of Finance. To protect the value of the dinar, the Bank must tighten its monetary policy, not expand it.

Mahmood Baban is a research fellow at the Rudaw Research Center.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of Rudaw.

Comments

Rudaw moderates all comments submitted on our website. We welcome comments which are relevant to the article and encourage further discussion about the issues that matter to you. We also welcome constructive criticism about Rudaw.

To be approved for publication, however, your comments must meet our community guidelines.

We will not tolerate the following: profanity, threats, personal attacks, vulgarity, abuse (such as sexism, racism, homophobia or xenophobia), or commercial or personal promotion.

Comments that do not meet our guidelines will be rejected. Comments are not edited – they are either approved or rejected.

Post a comment